This clipboard picture is more evidence of what I blogged about earlier this week — i.e. the visual effect that Instagram has wrought on me. I’ve probably used this clipboard dozens of times in the last few months, but when it was sitting on the kitchen table today I wondered what it would look like as a slightly altered picture. So I took a close-up, hit the “Lomo-fy” filter on Instagram, and boom: Whoa! I’d before never noticed the pattern of scratches, or the odd, teensy blobs of ink … or the crepuscular, grainy quality of the cardboardy wood. Duuude.

Do you ever experience chills while listening to music? Recently, scientists have gotten interested in this question, and they’ve found some fascinating stuff. While most people experience chills some of the time, a small minority experience them very frequently — and about 10% say they never feel chills.

What accounts for the difference? Is it based in the type of music you listen to — like punk or country or hip-hop? Or the type of person you are? Or maybe some complex combination of the two — i.e. maybe the type of people who listen to, say, mainstream pop are also the type of people most likely to feel chills in the presence of art they heavily dig?

To try and figure it out, Emily C. Nusbaum (a scientific name that totally freaked me out because it’s almost precisely that of my wife) and Paul J. Silvia decided to survey 196 students at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. They asked them how often they felt chills while listening to music; then they profiled their personalities using the “big five” scale (i.e. how they scored on measures of neuroticism, extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness). And finally they asked the students to describe how much they liked or hated various types of music based on the way music is categorized in the STOMP scale — which, for example, slots classic and folk music as “Reflective and Complex”, and rock and metal as “Intense and Rebellious”. (I kind of cracked up reading those STOMP categories. I mean, sure, yeah, technically Rachmaninoff is classical music — but it’s easily more “Intense and Rebellious” than, god save us, Nickelback. Meanwhile, Pachabel’s Canon, having become the go-to processional music for about seven trillion weddings, has been taxidermically drained of any serious reflective value. Anyway …)

The point is, once they crunched their data, no music genre trumped. There is no particular type of music you can listen to that will reliably impart chills. The truly big predictor? Your personality. Specifically, how open you are to experience — because this affects how frequently and deeply you engage with music. People who are more open to experience are also likely to interact with music in specifically intense ways:

In particular, rating music as more important, listening to music for more hours per day, and playing an instrument significantly predicted aesthetic chills.

Intuitively, this makes sense. Yet when I think about it, my own experience of music doesn’t really dovetail with these findings. I don’t know how high I score on measures of openness — I’ve never had myself tested — but I’ve played instruments most of my life (daily, in fact); I listen to music every day; but I don’t think I often experience chills.

Personally, I’d love for some researchers to do some even more ambitious research into chills. Why no trick out hundreds (thousands!) of listeners with software MP3 players for smartphones that lets then easily record precisely when you feel chills while listening to music. That way, you could capture what exact song provoked the chills — better yet, what passage in what song — as well as physically where you were located, what time of day, what else you were doing, and probably a bunch of other easily loggable data points.

The paper appears the October issue of Social Psychological and Personality Science, and is free online here!

(That photo is courtesy the Creative-Commons-licensed Flickr photostream of marimoon!)

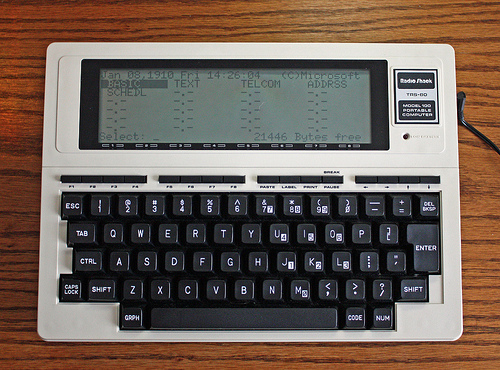

In October of 1962, Douglas Englebart imagined a remarkable new technology for writing. Englebart is a serial visionary; among other things, he’s famous for having invented the computer mouse. But in his essay “Augmenting Human Intellect”, he envisioned a typing machine that was also equipped with a special sensing stylus. It would work like this: You’d type away at the machine, composing notes or a raw draft of a piece. But after you’d written a bunch of stuff, you could sit back, read it over, and if you found a passage you wanted to clip out and reproduce, you could just wave the stylus over the words and — presto — they’d be re-typed by your machine.

He was, in essence, imagining a machine that could electronically cut and paste.

Englebart suspected cut-and-paste would have an enormous impact on the way we’d write. As he predicted:

This writing machine would permit you to use a new process of composing text. For instance, trial drafts could rapidly be composed from re-arranged excerpts of old drafts, together with new words or passages which you stop to type in. Your first draft could represent a free outpouring of thoughts in any order, with the inspection of foregoing thoughts continuously stimulating new considerations and ideas to be entered. If the tangle of thoughts represented by the draft became too complex, you would compile a reordered draft quickly. It would be practical for you to accommodate more complexity in the trails of thought you might build in search of the path that suits your needs.

Pretty amazing foresight, eh? He wrote that 50 years ago — when computers were still room-sized industrial tools — yet he nailed it: One of the biggest impacts of word processing has been the way it makes cutting and pasting a central part of how we organize our thoughts.

The funny thing is, cutting and pasting is now so routine that we often forget how strange it felt at first. I’m 42, old enough that I wrote my high-school essays — and even the essays of my first year of college — longhand on paper, then typed them up on a typewriter. The work of arranging and redacting my thoughts was done with a pencil and paper; the typewriter existed mostly just as a way to produce a good-looking final draft, though I’d occasionally buff or improve a sentence as I was typing it up. (Though I wouldn’t edit too much; if my attempts to tweak the sentence while typing made things worse, I’d have to laboriously white out my screwed-up text with Liquid Paper, a substance beyond foul.)

When I first got my hands on a word processor, it felt absolutely uncanny: The words! They’re … they’re moving around! THEY LOOK LIKE PRINTED WORDS BUT THEY’RE MOVING AROUND. But pretty quickly I grasped the new style of composition that was possible, and I loved it. Precisely as Englebart envisioned, I could write longer, more discursive drafts, letting my thoughts wander into ever-more-creative-or-weirder nooks, and taking arguments to their logical endpoint just to see where they’d lead. I could give myself mental permission to do this because it was easy to redact the best parts into my final essay. Robert Frost talked about how he couldn’t tell what a poem was going to be about until he’d finished writing it. That’s what word processors did to my academic and journalistic writing: As the mechanical act of writing became easier, it became easier to write prodigiously as a way of sussing out my own thoughts.

It’s hard to remember now, but many people back in the 80s totally freaked out about word processing. I recall professors worrying that it would make students write more sloppily, and even think more sloppily. The fluidity of cutting and pasting seemed intellectually suspicious. I even remember one of my TAs arguing — in a lovely foreshadowing of today’s fears that “the Internet is making us stupid” — that cutting and pasting would render our generation unable to craft a coherent argument, because the sheer slipperiness of digital prose, its slithy rearrangeability, would render our ideas and prose rootless, nonsequential, and flighty.

Mind you, they weren’t entirely wrong. Cut-and-paste poses cognitive risks that plague me even today. Sometimes when I’m working on a story, I’ll cut and paste so many bloated passages from white papers and interviews into my “research file” that it eventually metasasizes to the length of Infinite Jest, and becomes completely useless. (Fascinatingly, some scientific studies (PFD link) have found that the most high-performing students resist this impulse: During research, they’re more judicious in their use of cut-and-paste than their lower-performing peers.) And I also find there are times when I need to step away from word processing. When I’m blocked on a piece of writing — particularly when I need to do big-picture structural thinking about the shape of a long article — I often reach for a pencil and huge piece of paper, so I can diagram the flow. (And hey: There are word-processing holdouts even more hard-core, like the excellent sci-fi novelist Joe Halderman, who writes not only exclusively in longhand but by the light of oil lamps.)

It’s an interesting question either way. How has the word processor changed the way we think? How has it changed the way you think?

As a casualty — or side benefit (is it a bug? or a feature!) — of having read and written a metric ton of poetry in college, I still read a lot of poetry these days. And it’s surprising how often you come across poets who wrote decades, centuries or millennia ago, yet grappled with issues that seem absolutely contemporary.

Like microcelebrity! Two years ago I picked up a copy of Daniel Mendelsohn’s incredibly awesome new translations of the Greek poet C.P. Cavafy. It includes this rendition of “As Much As You Can”, a poem that Cavafy wrote in 1905, but reads like he’s talking about Facebook and Instagram today.

Normally I’d reprint the poem in ASCII text, but the screengrab from Amazon’s “Look Inside” is somewhat prettier, if fuzzier. I actually put this poem up on my tumblr a year ago, but I was rereading that collection of Cavafy again today and it struck me anew — particularly the dry irony of the title, which suggests the poem will urge the reader on to excess, when it’s actually about restraining yourself.

But there’s more! Below the jump, Emily Dickinson — the patron saint of shut-ins — meditating on Kim Kardashian!

That door above? It’s from a brownstone about three blocks from my house. It’s on the way to the subway and the local grocery store, so I’ve probably walked past it 100 times since I moved back to Brooklyn earlier this year.

But I never particularly noticed it. Why would I? There are about four trillion brownstones where I live, with doors just like this one.

Then a week ago, things changed when my friend Nick Bilton showed me the hot new mobile app-du-jour, Instagram. If you haven’t tried Instagram, it’s a brilliantly simple concept: You snap pictures on your phone, apply one of a dozen filters that work various forms of retro-izing algorithmic hoodoo — remaking them Lomo style, for example — after which you upload the pictures to your stream. Then it’s off to the social-media races! You subscribe to other folks’ photo streams, comment or “like” other photos, check out the trending “popular” photos, etcetera etcetera.

I was instantly, and horribly, hooked. Sure, I have lots of apps on my phone, and I check some of them very, very often. But my Instagram behavior verges into the realm of what one could more properly call tweaking. Apparently I’m not alone; after only one month in business, Instagram has already amassed well over 500,000 users. But why? What’s the allure?

As many have noted, some of Instagram’s appeal is that it’s so perfectly simple, with none of crufty bells and whistles that plague, say, Facebook. Instagram is simpler even than Flickr: As Faruk Ates pointed out, you’re not trying to collect and curate photos. You just see something and — boom — in about 15 seconds you’ve shared it with everyone in your network. And while, sure, there are photos on Facebook and Twitter, it turns out there’s something weirdly hypnotic about following the lives of your friends through nothing but images. Given that Instagram’s user base is very international (for now, anyway), the most-popular page of photos is like a constellation of slices-‘o-life from around the globe. About half the people I’m following are total strangers in Russia, Korea and Argentina who take strikingly cool pictures.

But for me, the really deep appeal of Instagram is more subtle: It changes the way I look at the world around me.

I’m not a super visual person; I do not normally take a lot of photos. But now I am, and do. Whenever you join a new social network, there’s this sudden, gentle pressure to, y’know, be more interesting. In the case of Twitter, that manifests itself as a pressure to post ever-more-cool undiscovered URLage. In the case of Instagram, it means posting ever-more-nifty snapshots. And this in turn means that I’ve begun looking at the world around me anew. I used to walk around my neighborhood blissfully — or stressfully — ignoring my surroundings, while staring at the sidewalk (or, ironically, my iphone). Now I find myself spotting unusual bits of graffiti, or patterns that fall trees make against the sky, or how super strange the robot is on Yo Gabba Gabba when my kids watch in the morning. Or that blue door on the brownstone in the picture above: How did I not notice how pretty it was? It’s like my third eye has opened up!

What’s more, I think Instagram’s image-altering filters are a key part of my visual awakening, because they often take meh photographs and render them newly weird, making me look at the subjects in a new way. Plenty of folks have critiqued the fad towards lo-fi photography on the iPhone (like the Hipstamatic), arguing that it harnesses nostalgia to make boring pictures seem artificially cool.

I’m sure that’s true for some people. But filtering makes me look at stuff with fresh eyes. The unaltered picture of that brownstone door was attractive enough; but after the Lomo filter I realized it reminded me of a Tardis. I began scrutinizing otherwise blasé stuff in my house, wondering, hmm, how would that look with a filter applied? This reached its apotheosis — or nadir, depending on how you look at it — a few days ago while taking out the trash, when I found myself regarding the decrepit lids of my plastic garbage cans in whoa-dude daze. I whipped out Instagram and discovered that — hey — the lids’ texture looks vaguely lunar if you strip out enough color detail. (Snapshots below the jump! For those who cannot wait to see my garbage-can lids.)

And this, really, is what I love most about new communications tools. At their best, they encourage us to pay attention to our lives in new ways.

I'm Clive Thompson, the author of Smarter Than You Think: How Technology is Changing Our Minds for the Better (Penguin Press). You can order the book now at Amazon, Barnes and Noble, Powells, Indiebound, or through your local bookstore! I'm also a contributing writer for the New York Times Magazine and a columnist for Wired magazine. Email is here or ping me via the antiquated form of AOL IM (pomeranian99).

ECHO

Erik Weissengruber

Vespaboy

Terri Senft

Tom Igoe

El Rey Del Art

Morgan Noel

Maura Johnston

Cori Eckert

Heather Gold

Andrew Hearst

Chris Allbritton

Bret Dawson

Michele Tepper

Sharyn November

Gail Jaitin

Barnaby Marshall

Frankly, I'd Rather Not

The Shifted Librarian

Ryan Bigge

Nick Denton

Howard Sherman's Nuggets

Serial Deviant

Ellen McDermott

Jeff Liu

Marc Kelsey

Chris Shieh

Iron Monkey

Diversions

Rob Toole

Donut Rock City

Ross Judson

Idle Words

J-Walk Blog

The Antic Muse

Tribblescape

Little Things

Jeff Heer

Abstract Dynamics

Snark Market

Plastic Bag

Sensory Impact

Incoming Signals

MemeFirst

MemoryCard

Majikthise

Ludonauts

Boing Boing

Slashdot

Atrios

Smart Mobs

Plastic

Ludology.org

The Feature

Gizmodo

game girl

Mindjack

Techdirt Wireless News

Corante Gaming blog

Corante Social Software blog

ECHO

SciTech Daily

Arts and Letters Daily

Textually.org

BlogPulse

Robots.net

Alan Reiter's Wireless Data Weblog

Brad DeLong

Viral Marketing Blog

Gameblogs

Slashdot Games