« PREVIOUS ENTRY

The art of public thinking

Yesterday I was poking around on Instagram, and one of the people I follow put up a picture of the Canadian National Exhibition.

If you’ve never been to it, the CNE is pop-up amusement park that is enormously fun but, unusually by Canadian standards, extraordinarily seedy. Much like a backwater US county fair, it’s got rides operated by creepy-looking dudes who appear to be on weekend leave from a minimum-security prison; inedible funnel cakery; and “skill” games where the top prize is a refrigerator-sized Pikachu, the label of which frantically assures you that the stuffing is “new”. At any rate, this is how I remember it from my youth in the late 70s and early 80s. It may have cleaned up its act since, but I sort of hope not; I enjoyed the sense of Caligulan decay.

When I saw the CNE Instagram picture, I noticed the Instagrammer had tagged it — with #cne — and that clicked through to a constellation of 517 pictures, all taken in the last day or so. (That’s them, above.) This was Proustian stuff; it brought me right back to childhood! The Crazy Mouse ride, teetering on its improbably tiny rails! The ferris wheel aglow at night! The goats! (At the CNE there’s a building devoted, with steadily mounting anachronism, to local Canadian farming.)

And those tagged pictures made me think of a book I’d just finished reading earlier that same day: The Augmented Mind by Derrick de Kerckhove. De Kerckhove was a colleague of Marshall McLuhan back in the day, and he still carries his intellectual torch. Now, if you’ve read any Marshall McLuhan or Harold Innis — McLuhan’s lesser-known but kind-of-cooler Canadian economist intellectual midwife — you’ve no doubt mused on how different communication tools influence us. Innis called it the “bias” inherent in each form of communication. McLuhan rebranded that concept as “the medium is the message”, the much-catchier phrasing, but they both push the same idea: That how a medium functions is far more interesting and powerful than the content that travels over it. So for McLuhan, the real impact of electricity was the emergence of simultaneity, the real impact of print was linearity, etc. (Newspapers didn’t much impress him: “Today’s press agent regards the newspaper as a ventriloquist does his dummy.” That was 1964!)

Today you could ask: What’s the “bias” of the Internet? Plenty of ink has been spilled on this subject, but almost nobody uses Innis’ obscure terminology. So I was thus intrigued earlier this week when I stumbled upon an interview in which de Kerchkove used precisely that phrasing. He was talking about why he wrote The Augmented Mind, and said …

“Still in line with the Toronto School of Communications approach, I was trying to identify the bias of the medium of the Internet.

The Internet’s core principle of operation is packet switching. I found that for packet switching to carry the information in the right order to the right place, the precision of the whole system was owed to a unique way of dividing the information into short strings (or packets) and addressing each one with its unique label and position in the sequence to reconstruct the message wherever needed. That, in essence is the tag. Without the possibility to isolate, identify, and connect each packet there would neither Internet nor World Wide Web. Tagging hence by making any information available on demand is the core, the soul of the Internet. Tags allow to connect analog to digital media, and to interconnect everything with everything else end-to-end on demand. We are today in the midst of what I have called the era of the tag.”

A provocative idea! Alas, de Kerckhove doesn’t actually unpack this very much in the book itself, other than to offer up that neatly McLuhanesque koan: “A tag is the soul of the Internet.” But I dig the fractal quality of it. Tags are how everything online — from packets on up to entire documents — are recombined and made new sense of.

What’s particularly cool, for me, is that this makes re-interesting a tool that had become pretty blasé: The tag. Sure, tagging was intellectually hot six or seven years ago when people first began affixing them en masse to blog posts, bookmark links, Flickr pictures, and eventually tweets. And for a while there was the conversation about “folksonomy”, the way that mass tagging was more disorganized than formal library taxonomies (I call that photo “my_adorable_cat”; you call it “cloying”) but it allowed for very rapid organization and sorting of online stuff. But this is where tags quickly began to seem rather humdrum to me — just a piece of plumbing in everyday online life. You visit a tumblr site, use the tags to quickly sort through a bunch of posts. Big whoop.

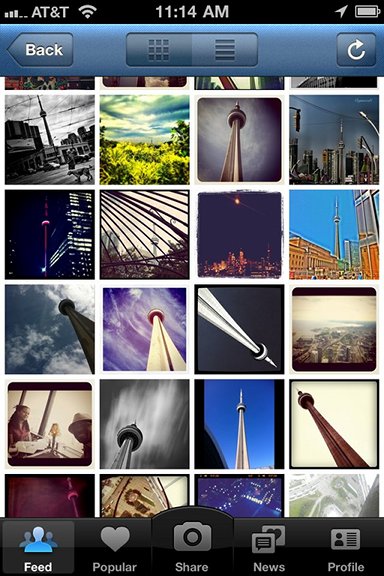

But yesterday I started clicking around on those Instagram tags. (For the first time, actually: I am probably the last Instagram user on the planet to realize they were there.) And all of sudden I found them surprisingly affecting and powerful. Why? Probably because Instagram’s content is visual. The tags create a sort of “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird” effect: You see the same scene over and over again, but through many people’s different viewpoints. In the constellation of CNE images above, one person picks out the massive creepy clown head; another, the “Epic Burgers”; another, the goat. While poking around in the pictures, I noticed the CN Tower lurked in the background — Toronto’s famous landmark — and the photographer had tagged it. So I clicked that tag and boom, I got the same experience of multiply re-seeing the CN Tower:

I like these different views: It’s a tourist trap, a play of light, a bow-chicka-bow phallic piece of 1970s architecture, and even a barely-noticeable spec in the distance when you’re out in the Toronto countryside.

Here’s another thing: The perceptual effect is of all these tagged photos is really strengthened by Instagram’s filters. If you see a zillion pictures of the same statue on Flickr, you’re like, oh, cool, interesting. But here, the filters make each point of view seem somehow more different and more alien from the others. And here’s another fun time-waster I got sucked into: Surfing the tags for the filters themselves. Each filter has a name; “Earlybird” is the one that sort of blows up the light in the center of the picture, mutes the colors, and rounds the edges of the picture. So when someone tags their photo with “Earlybird” you click on it and wind up seeing the inverse of the 13-blackbirds effect: Instead of viewing a single scene through many differently-filtered views, you see lots of different things — a car, two people kissing, a garbage can, a plane flying overhead — all filtered the same way: The world viewed from the perspective of the filter Earlybird, as it were.

Okay, enough of these stoner epiphanies! The point is that Instagram’s tags, primed by de Kerckhove’s provocation, made me think anew about the cognitive power of tags — their sense-making ability. But I also realized I haven’t seen designers do anything particularly interesting with tags in a while. I haven’t seen anything that helps me spy patterns in data/documents/pictures in similarly weird and fresh ways. Maybe tagging, as a discipline, hasn’t been pushed in very interesting ways. Or maybe I haven’t been looking in the right place?

(Irony of ironies, I realize I’ve never bothered to tag my blog posts.)

I'm Clive Thompson, the author of Smarter Than You Think: How Technology is Changing Our Minds for the Better (Penguin Press). You can order the book now at Amazon, Barnes and Noble, Powells, Indiebound, or through your local bookstore! I'm also a contributing writer for the New York Times Magazine and a columnist for Wired magazine. Email is here or ping me via the antiquated form of AOL IM (pomeranian99).

ECHO

Erik Weissengruber

Vespaboy

Terri Senft

Tom Igoe

El Rey Del Art

Morgan Noel

Maura Johnston

Cori Eckert

Heather Gold

Andrew Hearst

Chris Allbritton

Bret Dawson

Michele Tepper

Sharyn November

Gail Jaitin

Barnaby Marshall

Frankly, I'd Rather Not

The Shifted Librarian

Ryan Bigge

Nick Denton

Howard Sherman's Nuggets

Serial Deviant

Ellen McDermott

Jeff Liu

Marc Kelsey

Chris Shieh

Iron Monkey

Diversions

Rob Toole

Donut Rock City

Ross Judson

Idle Words

J-Walk Blog

The Antic Muse

Tribblescape

Little Things

Jeff Heer

Abstract Dynamics

Snark Market

Plastic Bag

Sensory Impact

Incoming Signals

MemeFirst

MemoryCard

Majikthise

Ludonauts

Boing Boing

Slashdot

Atrios

Smart Mobs

Plastic

Ludology.org

The Feature

Gizmodo

game girl

Mindjack

Techdirt Wireless News

Corante Gaming blog

Corante Social Software blog

ECHO

SciTech Daily

Arts and Letters Daily

Textually.org

BlogPulse

Robots.net

Alan Reiter's Wireless Data Weblog

Brad DeLong

Viral Marketing Blog

Gameblogs

Slashdot Games