NEXT ENTRY »

Garry Kasparov, cyborg

My latest column for Wired magazine is now online, and it’s a fun topic: I analyze the downside of becoming Twitter famous. You can read the full text below — or for free at Wired’s site, or in print if you race out to a newsstand this very instant and pick up a copy! — but the gist of the argument is simple: If you have too many followers, the conversational and observational qualities that originally make Twitter fun start to break down … and you’re left with old-fashioned (and often quite dull) broadcasting.

If you like the column, go check out Anil Dash’s excellent blog post “Life on the List”. He describes what it’s like being put on Twitter’s “Suggested User” list — i.e. the list that Twitter publishes that recommends interesting people to follow. Those who are put on the list quickly begin amassing thousands of followers a day, which is precisely what happened to Anil, who now has over 327,000 people following him. And Anil encountered precisely the phenomenon I described: He didn’t like it, and thinks it partly ruined his experience of Twitter.

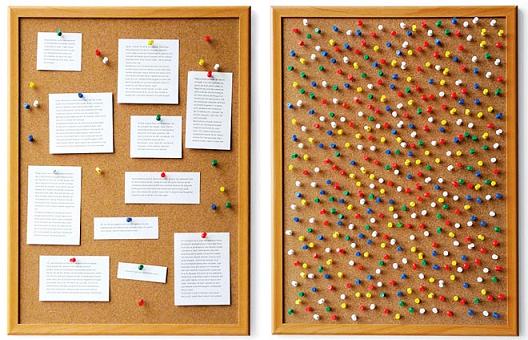

Anyway, read on! (That picture above, by the way, is the lovely illustration by Helen Yentus and Jason Booher that appears in the print copy of Wired.)

In Praise of Obscurity

by Clive ThompsonWhen it comes to your social network, bigger is better — or so we’re told. The more followers and friends you have, the more awesome and important you are. That’s why you see so much oohing and aahing over people with a million Twitter followers.

But lately I’ve been thinking about the downside of having a huge online audience. When you go from having a few hundred Twitter followers to ten thousand, something unexpected happens: Social networking starts to break down.

Consider the case of Maureen Evans. A grad student and poet, Evans got into Twitter at the very beginning — back in 2006 — and soon built up almost 100 followers. Like many users, she enjoyed the conversational nature of the medium. A follower would respond to one of her posts, other followers would chime in, and she’d respond back.Then, in 2007, she began a nifty project: tweeting recipes, each condensed to 140 characters. She soon amassed 3,000 followers, but her online life still felt like a small town: Among the regulars, people knew each other and enjoyed conversing. But as her audience grew and grew, eventually cracking 13,000, the sense of community evaporated. People stopped talking to one another, or even talking to her. “It became dead silence,” she marvels.

Why? Because socializing doesn’t scale. Once a group reaches a certain size, each participant starts to feel anonymous again, and the person they’re following — who once seemed proximal, like a friend — now seems larger than life and remote. “They feel they can’t possibly be the person who’s going to make the useful contribution,” Evans says. So the conversation stops.

Evans isn’t alone. I’ve heard this story again and again from those who’ve risen into the lower ranks of microfame. At a few hundred or a few thousand followers, they’re having fun — but any bigger and it falls apart. Social media stops being social. It’s no longer a bantering process of thinking and living out loud. It becomes old-fashioned broadcasting.

The lesson? There’s value in obscurity.

After all, the world’s bravest and most important ideas are often forged away from the spotlight — in small, obscure groups of people who are passionately interested in a subject and like arguing about it. They’re willing to experiment with risky or dumb concepts because they’re among intimates. (It was, after all, small groups of marginal weirdos that brought us the computer, democracy, and the novel.)

Technically speaking, online social-networking tools ought to be great at fostering these sorts of clusters. Blogs and Twitter and Facebook are, as Internet guru John Battelle puts it, “conversational media.” But when the conversation gets big enough, it shuts down. Not only do audiences feel estranged, the participants also start self-censoring. People who suddenly find themselves with really huge audiences often start writing more cautiously, like politicians.

When it comes to microfame, the worst place to be is in the middle of the pack. If someone’s got 1.5 million followers on Twitter, they’re one of the rare and straightforwardly famous folks online. Like a digital Oprah, they enjoy a massive audience that might even generate revenue. There’s no pretense of intimacy with their audience, so there’s no conversation to spoil. Meanwhile, if you have a hundred followers, you’re clearly just chatting with pals. It’s the middle ground — when someone amasses, say, tens of thousands of followers — where the social contract of social media becomes murky.

Maybe we should be designing tools that reward obscurity — that encourage us to remain in the shadows. Or what if they warned us when our social circles became unsustainably large? Sure, we’d be connected with fewer people, but we’d be communicating with them, and not just talking at them.

I'm Clive Thompson, the author of Smarter Than You Think: How Technology is Changing Our Minds for the Better (Penguin Press). You can order the book now at Amazon, Barnes and Noble, Powells, Indiebound, or through your local bookstore! I'm also a contributing writer for the New York Times Magazine and a columnist for Wired magazine. Email is here or ping me via the antiquated form of AOL IM (pomeranian99).

ECHO

Erik Weissengruber

Vespaboy

Terri Senft

Tom Igoe

El Rey Del Art

Morgan Noel

Maura Johnston

Cori Eckert

Heather Gold

Andrew Hearst

Chris Allbritton

Bret Dawson

Michele Tepper

Sharyn November

Gail Jaitin

Barnaby Marshall

Frankly, I'd Rather Not

The Shifted Librarian

Ryan Bigge

Nick Denton

Howard Sherman's Nuggets

Serial Deviant

Ellen McDermott

Jeff Liu

Marc Kelsey

Chris Shieh

Iron Monkey

Diversions

Rob Toole

Donut Rock City

Ross Judson

Idle Words

J-Walk Blog

The Antic Muse

Tribblescape

Little Things

Jeff Heer

Abstract Dynamics

Snark Market

Plastic Bag

Sensory Impact

Incoming Signals

MemeFirst

MemoryCard

Majikthise

Ludonauts

Boing Boing

Slashdot

Atrios

Smart Mobs

Plastic

Ludology.org

The Feature

Gizmodo

game girl

Mindjack

Techdirt Wireless News

Corante Gaming blog

Corante Social Software blog

ECHO

SciTech Daily

Arts and Letters Daily

Textually.org

BlogPulse

Robots.net

Alan Reiter's Wireless Data Weblog

Brad DeLong

Viral Marketing Blog

Gameblogs

Slashdot Games