« PREVIOUS ENTRY

Viewing massive accidents using Google Maps

By now, it’s pretty obvious that there is lots of fakery in online reviews. Most of the time, I assume the faking skews positive: i.e. a manufacturer Turks a bunch of people to write glowing assessments of their widget on Amazon; an author goes all sprezzatura and pens delirious self-praise via a network of sock puppets.

But it turns out there are also faked bad reviews — people who trashtalk a product even though they haven’t actually used it or bought it themselves.

Better yet — it’s possible to recognize faked bad reviews. According to a fascinating study recently released, faked bad reviews carry several linguistic markers of their fakeitude: They’re vaguely worded, longer than other reviews, and have lots of exclamation points!!!!

If you’re in a hurry and wanna read the bullet-pointed takeaways, skip down to the middle of this entry.

But for those of you awesome people who love to read about clever data-collection protocols, here’s some background on the study. It opens with an interesting question: How do you analyze faked bad reviews?

Well, for starters, you have to collect a bunch of them. In other words, you have to gather up a bunch of negative reviews written by people who you know didn’t buy the product. Eric Anderson of Northwestern University and Duncan Simester of MIT hit upon an elegant way to accomplish this. They got the co-operation of an online brand (unnamed) that sells its products direct to customers — via stores and online — and, what’s more, only sells them direct; it doesn’t sell via any other channels, like big chains. With this brand, either you buy from them directly or you don’t buy it at all.

Now, this brand also carefully tracks its online customers. You need to register to purchase something from the web site, so the brand knows precisely what every online customer has and hasn’t bought. Crucially, the brand also links its customers’ in-store purchases to their online purchasing identities, so the company knows what each customer has bought both in meatspace and on the intertubes. What’s more, to review something on the site you have to be signed in — there are no anonymous reviews. The brand knows precisely who wrote what.

With this info, the researchers could isolate the “faked” bad reviews on the site — i.e. the situations in which a customer reviewed a product that they manifestly had bought neither online nor (with reasonable certainty) offline. Anderson and Simester found 15,759 such reviews. Interestingly, these reviews were not written by drive-by cranks who signed up for the site just to post trash talk. No, the fake bad reviews were written by avid customers — people who had, in the past, bought plenty of items from the brand. But in this case they’d for some reason reviewed an item without having bought it.

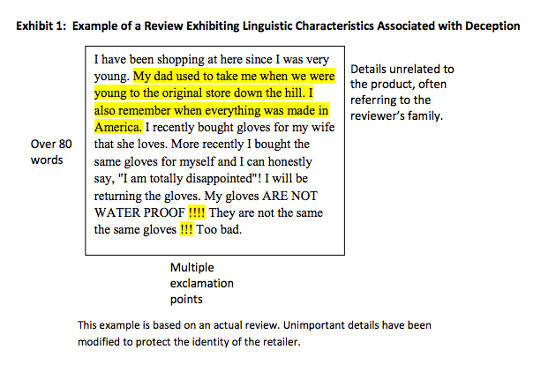

When the researchers analyzed the language traits of these faked negative reviews, several trends things emerged. The differences between faked and non-faked bad reviews aren’t huge, but they’re consistent. Here’s my redaction of the big ones the researchers found:

- They’re long. “Perhaps the strongest cue associated with deception is the number of words: deceptive messages tend to be longer” — about 36%, on average. Fake ones were on average 70.13 words long; authentic negative reviews were only 52 words. Why is this? Because, as psychologists have long documented, it’s harder to craft a lie than to tell the truth.

- They’re vague. Since the reviewers here are assessing goods they haven’t actually touched or felt, “these reviews are significantly less likely to include descriptions of the fit or feel of the garments, which can generally only be evaluated through physical inspection.”

- They contain irrelevant details. Fake reviewers were more likely to fill up their prose with seemingly off-point discussions of stuff not germane to the product — such as mentions of their family. “They are also more likely to contain details unrelated to the product (‘I also remember when everything was made in America’) and these details often mention the reviewer’s family (‘My dad used to take me when we were young to the original store down the hill’).”

- And my personal favorite mark of inauthenticity: “multiple exclamation points.”

Now, there are plenty of caveats with this study. It’s possible that some of the reviews weren’t actually fake. Maybe the reviewer got ahold of the product in some fashion outside the detectable stream of purchases, such as in a gift or Ebay; or maybe the brand’s system of tying the physical-store purchases to online purchases isn’t complete enough. The researchers claim they’ve ruled these out as best as possible, and while they were clearly quite careful, there’s always room for error. It’s not published and peer-reviewed work.

Nonetheless, if you grant the force of this analysis, it leads to a fun question Why do customers write fake negative reviews?

Again, these aren’t just a bunch of randos who hate the brand and are just doing it for the lulz. On the contrary, they’re loyal customers: Anderson and Simester found that writers of fake negative reviews continue to buy lots of products from the brand — indeed, slightly moreso than people who don’t write fake negative reviews. The researchers offer a different hypothesis:

The explanation that is most consistent with the data is that these are loyal customers acting as self-appointed brand managers. The review process provides a convenient mechanism for them to give feedback to the firm … They are loyal to the brand and want an avenue to provide feedback to the company about how to improve its products. They will even do so on products they have not purchased.

Evidence of this? Fake reviews are three times more likely than non-fake reviews to use language that indicates they’re talking to the company directly. In a “real” review, the author writes phrases like “if you are looking,” “if you need,” or “if you want”. In other words, they’re addressing other customers. But the faked reviews used phrases like “bring back,” “offer more,” or “carry more”. They were writing for an audience of the company — using the negative review to hector/lecture the brand directly.

It’s pretty fascinating stuff. It’s going to get me to look twice at negative reviews now.

The full paper — “Deceptive Reviews: The Influential Tail” — is here.

I'm Clive Thompson, the author of Smarter Than You Think: How Technology is Changing Our Minds for the Better (Penguin Press). You can order the book now at Amazon, Barnes and Noble, Powells, Indiebound, or through your local bookstore! I'm also a contributing writer for the New York Times Magazine and a columnist for Wired magazine. Email is here or ping me via the antiquated form of AOL IM (pomeranian99).

ECHO

Erik Weissengruber

Vespaboy

Terri Senft

Tom Igoe

El Rey Del Art

Morgan Noel

Maura Johnston

Cori Eckert

Heather Gold

Andrew Hearst

Chris Allbritton

Bret Dawson

Michele Tepper

Sharyn November

Gail Jaitin

Barnaby Marshall

Frankly, I'd Rather Not

The Shifted Librarian

Ryan Bigge

Nick Denton

Howard Sherman's Nuggets

Serial Deviant

Ellen McDermott

Jeff Liu

Marc Kelsey

Chris Shieh

Iron Monkey

Diversions

Rob Toole

Donut Rock City

Ross Judson

Idle Words

J-Walk Blog

The Antic Muse

Tribblescape

Little Things

Jeff Heer

Abstract Dynamics

Snark Market

Plastic Bag

Sensory Impact

Incoming Signals

MemeFirst

MemoryCard

Majikthise

Ludonauts

Boing Boing

Slashdot

Atrios

Smart Mobs

Plastic

Ludology.org

The Feature

Gizmodo

game girl

Mindjack

Techdirt Wireless News

Corante Gaming blog

Corante Social Software blog

ECHO

SciTech Daily

Arts and Letters Daily

Textually.org

BlogPulse

Robots.net

Alan Reiter's Wireless Data Weblog

Brad DeLong

Viral Marketing Blog

Gameblogs

Slashdot Games