Are young people who use landlines more conservative than young people who use mobile phones?

Apparently so, according to the Pew Research Center for the People & the Press. The Pew project recently got interested the question of whether the explosive growth of mobile phones is making traditional polls irrelevant. Political polls generally only use landlines to collect their data, but young people — classified as those “under 30” — are more and more foregoing landlines in favor of using only a mobile phone. (As my last blog entry documented, only 1% of incoming students at Amherst college have a landline.) Since young people are also much more likely to be Democratic, the armchair critique is that traditional landline polls underreport Democratic support across the country, and overreport Republican support.

Is this really true, though? A group of Pew researchers decided to test the hypothesis. So they did three polls this year in which 20-25% of the people polled were reached by mobile phone — and then they compared them to polls done purely via landline. The conclusion? Sure, the mobile-phone people were much younger and more Democratic. But because traditional landline polls are weighted to compensate for age and other demographic differences, they were already pretty well capturing the youthquake. When the Pew people added in the mobile-phone interviewees, it didn’t change the poll results more than 2%, which is within the margin of errror. “In each of the surveys, there were only small, and not statistically significant, differences between presidential horserace estimates based on the combined interviews and estimates based on the landline surveys only,” as the Pew researchers wrote in a report on their findings two days ago.

So, all’s good, right? For now, possibly. But along the way, the Pew people found something different, and really fascinating:

Young people who use landlines are more likely to be Republican than young people who use mobile phones.

They discovered this when they pooled all the under-30s who been polled via landline and compared them to the under-30s who’d been reached on their mobiles. As the Pew researchers report …

… cell-only young people are considerably less likely than young people reached by landline to identify with or lean to the Republican Party, and even less likely to say they support John McCain. Among landline respondents under age 30, there is an 18-point gap in party identification - 54% identify or lean Democratic while 36% are Republican. Among the cell-only respondents under age 30, there is a 34-point gap - 62% are Democrats, 28% Republican. The difference among registered voters on the horserace is similar: 39% of registered voters under 30 reached by landline favor McCain, compared with just 27% of cell-only respondents. Obama is backed by 52% of landline respondents under 30, compared with 62% of the cell-only.

The researchers didn’t offer any hypothesis as to why this would be so, but it’s kind of interesting to speculate, eh? Why precisely would mobile-only youngsters be more Democratic than their peers who use landlines? What sort of ideological, psychological or personality elements underpin a desire to avoid landlines, and stick to mobiles?

It’s worth figuring out, because in the long run it will begin to affect landline polls. Why? Because, as the Pew researchers note:

Traditional landline surveys are typically weighted to compensate for age and other demographic differences, but the process depends on the assumption that the people reached over landlines are similar politically to their cell-only counterparts. These surveys suggest that this assumption is increasingly questionable, particularly among younger people.

Emphasis mine. Interesting stuff, either way!

(That photo above is courtesy arbyreed’s Creative Commons Flickr photostream!)

Peter Schilling — the director of information technology at Amherst College — crunched the numbers on the technological habits of this year’s incoming class, and discovered some fascinating stuff. He’s published it online as the “IT Index”, crafted in the style of a Harper’s Index, and it’s an intriguing snapshot of some of the technologically-driven behavioral changes that will mark the next generation.

Below are a few of my favorite stats, culled from the list. As you read, keep in mind that this incoming class has 438 students in it:

Percentage of first-year applicants who applied online in 2003: 33%.

Percentage of applicants who did last year: 89%.

By the end of August 2008 the total number of members and posts at the Amherst College Class of 2012 Facebook group: 432 members and 3,225 posts.

Students in the class of 2012 who registered computers, IPhones, game consoles, etc. on the campus network by the end of the day on August 24th, the day they moved into their dorm rooms: 370 students registered 443 devices.

Number of students in the class of 2012 who brought desktop computers to campus: 14.

Likelihood that a student with an iPhone/iTouch is in the class of 2012: approximately 1 in 2.

Total number of students on campus this year that have landline phone service: 5.

Mac or PC? Of the four classes currently on campus the classes of 2009 and 2010 are more likely to own Windows, while the classes of 2011 and 2012 are more likely to own Macs.

Okay, so, landlines are now officially a dead-man-walking technology: Only 1.1% of kids today have one. Meanwhile, Facebook has achieved precisely the opposite: A completely insane level of market penetration, at 98.63%. And Steve Jobs? Your work here is done.

Granted, the landline result is no doubt skewed by the fact that students who are only spending eight months a year on campus are less likely to get a personal landline in the first place, even absent the existence of mobile phones. But still, it’s a pretty remarkable death knell for a technology.

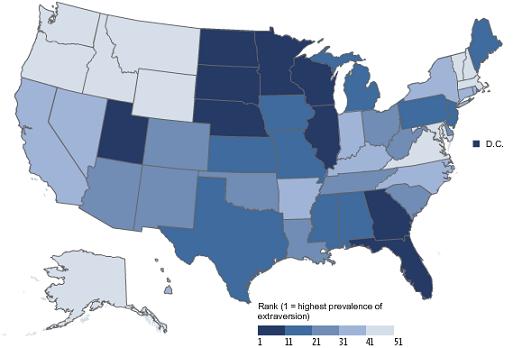

I’m coming a bit late to this one — it’s been heavily blogged in the last day or two — but it’s so lovely I can’t pass it up. A team of scientists have produced a map of the “geography of personality” in the US: What sorts of people cluster in what states.

Specifically, it used a standard personality test that rates people based on the “big five” personality traits — extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism and openness. The results? Highly conscientious states were a really mixed bag, including New Mexico, North Carolina, Utah and Florida. Super neurotic states included not only the obvious culprits — New York and New Jersey — but also Mississippi, Louisiana and Arkansas (the latter three possibly, the scientists surmise, because of the extremes of poverty found there).

As a story in the Wall Street Journal reports:

While the findings broadly uphold regional stereotypes, there are more than a few surprises. The flinty pragmatists of New England? They’re not as dutiful as they may seem, ranking at the bottom of the “conscientious” scale. High scores for openness to new ideas strongly correlates to liberal social values and Democratic voting habits. But three of the top ten “open” states — Nevada, Colorado and Virginia — traditionally vote Republican in presidential politics. (All three are prime battlegrounds this election.)

And what of the unexpected finding that North Dakota is the most outgoing state in the union? Yes, North Dakota, the same state memorialized years ago in the movie “Fargo” as a frozen wasteland of taciturn souls. Turns out you can be a laconic extrovert, at least in the world of psychology. The trait is defined in part by strong social networks and tight community bonds, which are characteristic of small towns across the Great Plains. (Though not, apparently, small towns in New England, which ranks quite low on the extraversion scale.)

The Journal put together a very cool interactive map that shows the results for each major personality type. The academic study itself — “A Theory of the Emergence, Persistence, and Expression of Geographic Variation in Psychological Characteristics” — is online behind a paywall here.

Obviously, there are a zillion cavaets here, including the fact that a lot of psychologists think personality tests are a bunch of hooey (though the “big five” test has gained more respect in recent years). What’s more, even if you grant the force of the test results, no one — not even the authors — can figure out whether the state “personality” emerges because of environmental factors or simply because people who are already pretty neurotic tend to move to New York.

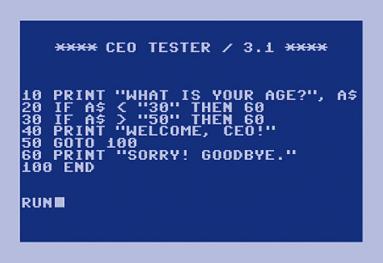

Are all breakthrough high-tech startups founded by young turks? You’d think so, based on youthquake hype in the tech media. But apparently the data say otherwise: According to a recent study, the average age of high-tech CEOs who found companies in the US is … 39.

I used this bit of research as the jumping-off point for my latest column in Wired magazine, which is on the newsstands now. You can read it for free at Wired’s site — or better yet, buy a print copy! — and I’ve put a permanent archival copy below.

(That excellent graphic above accompanied the article, and was created by Todd Albertson!)

Why Veteran Visionaries Will Save the World

by Clive Thompson

Don’t trust anyone over 30. That’s the prevailing wisdom in Silicon Valley, a land once again bestrode by millionaire CEOs who just learned to shave. Many people believe that the breakthrough ideas come only from the young. And why not? Media stories constantly recite the ages of a few famous founders: Bill Gates of Microsoft, 20; Mark Zuckerberg of Facebook, 20; the Google boys, 25; YouTube’s Chad Hurley, 28. Tumblr founder David Karp is 21 — and on his second successful company.

Young people rule tech innovation, we tell ourselves, because they have several key advantages. They’re fearless and naive, so they’ll try anything. They can spy markets that elders, with their locked-in views, cannot. And without dependents or spouses, twentysomethings can work the sort of pyramid-building hours necessary for a startup. It’s a kind of Logan’s Run world: If you’re ending a third decade, you’re obsolete.

But hold on. A recent study has finally collected some data on age and high tech innovation and found that older geeks are just as successful as young Turks. What’s more, the chronologically advanced are especially successful at solving problems we increasingly — and desperately — need solved.

In other words, the high tech future may belong to the over-30 set.

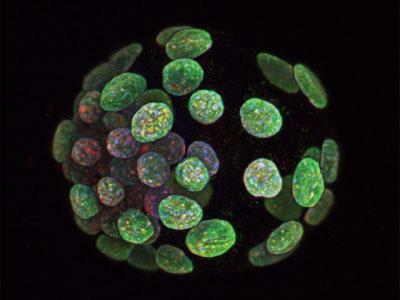

For 30 years, Nikon has held its “Small World” competition, which gives awards to the year’s best examples of photomicrography — snapshots of microscopic thingies. Their official judges have already met, and on Oct. 15 Nikon will announce the winning images.

But Nikon is also holding a public vote: You can go to their web site, view all 115 of the finalists, and vote for your favorite! That picture above is my fave — it’s an image of a mouse blastocyst taken by Dr. Fatima Santos of the Laboratory of Developmental Genetics and Imprinting in Cambridge, U.K. It looks like some sort of sentient alien cloud-being!

Wired News just published my latest video-game column, and this one compares the design of a video game to the design of American democracy. And vice versa!

A copy is free online at Wired’s site, and an archival copy is below:

The Game of Politics Is Ready for Its Upgrade

by Clive Thompson

I won the White House for Barack Obama last week. And for John McCain, too!

I was playing The Political Machine 2008, this year’s big sim-election title, and had a blast slinging mud and pandering. Playing as Obama, I stormed around the coasts, promising clean coal and running ads blasting McCain for supporting the war, and soon I was kicking back in the Oval Office. Playing as McCain, I played precisely the opposite cards in the red heartland, and won that race as well.

And as I turned off the computer, I thought — wow, you could regard The Political Machine as the supreme indictment of American Democracy. Because for all its cartoony graphics, the electioneering feels quite realistic. Almost too realistic. And you wind up worrying: Is real-life politics just a game, too?

I didn’t realize this, but Suzanne Vega is known as the “the mother of the MP3”, because Karl-Heinz Brandenberg — one of the audio engineers who developed the compression method — used Vega’s song “Tom’s Diner” as the reference track as he worked. “Tom’s Diner” is purely a capella and has minimal reverb, so Brandenberg thought it was the perfect gold standard: If his MP3 algorithm could compress the song without destroying its lovely timbre, he’d knew he’d have succeeded. As a result, he listened to “Tom’s Diner” thousands and thousands of times as he tweaked. The first compressions had “monstrous” distortions, but he kept at it until it was — to his ears — perfect.

Perfect to his ears — but not, apparently, to Suzanne Vega’s. Vega just published a wonderful essay on the New York Times’ web site where she describes visiting Brandenberg’s lab in 2001. As she writes:

The day I visited — “The Mother of the MP3 comes to the home of the MP3!” said the woman in charge of press (the slightly weird implication being that I would be meeting the various “fathers” of the MP3) — we had a press conference at which they played me the original version of “Tom’s Diner,” then the various distortions of the MP3 as it had been, which sounded monstrous and weird. Then, finally, the “clean” version of “Tom’s Diner.”

The panel beamed at me. “See?” one man said. “Now the MP3 recreates it perfectly. Exactly the same!”

“Actually, to my ears it sounds like there is a little more high end in the MP3 version? The MP3 doesn’t sound as warm as the original, maybe a tiny bit of bottom end is lost?” I suggested.

The man looked shocked. “No, Miss Vega, it is exactly the same.”

“Everybody knows that an MP3 compresses the sound and therefore loses some of the warmth,” I persisted. “That’s why some people collect vinyl…” I suddenly caught myself, realizing who I was speaking to in front of a roomful of German media.

Heh. Vega points out that although she is herself pretty computer illiterate, her life has some remarkable intersection points with high-tech development. For example, her mother was a computer scientist who used to drag a seriously old-school modem — “the size of a small refrigerator” — home so she could log into the Hunter College library from her kitchen. Then, in 1990, DNA — a two-man producer team — produced one of the first commercially successful folk-music remixes, by setting “Tom’s Diner” to an R&B dance track.

There’s an even cooler scientific coincidence that Vega doesn’t note. “Tom’s Diner” is based on the real-life Tom’s Restaurant, which Vega used to eat at in the 80s; it sits at 112th and Broadway in Manhattan and is famous, as Vega explains, for being the exterior shot of the diner in Seinfeld. But it’s also downstairs from a huge NASA lab — the Goddard Institute for Space Studies! It’s where NASA produces some of its most authoritative climate-change simulations; in fact, it’s the headquarters of James Hansen, the NASA scientist famous for predicting global warming twenty years ago.

(That photo of Vega above is courtesy possan’s Creative Commons photostream on Flickr! And thanks to Morgan for correcting me: The real-life version of “Tom’s Diner” is called Tom’s Restaurant.)

This month, Esquire celebrated its 75th anniversary by publishing the world’s first magazine cover with e-ink — a trippy little display that blinks and pulses (video above). It’s super cool-looking, and hackers have been trying to figure out how to tinker with it. To show off the technical challenges of producing the cover, Esquire put together a set of maps showing the globe-trotting path the various components traveled before they were assembled.

This led a few smart critics to ask a pertinent question: What the heck is the environmental cost of e-ink? Over at the Fast Company blog, Anya Kamenetz did some back-of-the-envelope calculations of the C02 emitted in producing the hardware and schlepping it all over the planet. Her conclusion:

So… the total outlay in greenhouse gas emissions for this little experiment — again, this is based on loose estimates — comes to 150 tons of CO2 equivalent, similar to the output of 15 Hummers or 20 average Americans for an entire year, and a 16% increase over the carbon footprint of a typical print publication (based on calculations by Discover Magazine, Time, and In Style). The potential environmental impact of the E Ink covers increases even more when you consider that the units are designed to be disposable after one use and they’ll make it more difficult or impossible to recycle the paper portion of the magazines.

Meanwhile, my friend Tom Igoe — a professor at New York University’s Interactive Telecommunications Program — quotes sections of Esquire’s description of the production cycle and marvels at the astonishing amounts of chemical waste. From his blog:

“Shanghai, China. The issue’s display screen, electronics, and batteries are assembled here, using components made in at least seven different factories.”

As opposed to one printing factory.

“Hurdles overcome include flooding that destroyed 250,000 batteries,”

When those find their way downstream and corrode because they weren’t disposed of properly, what chemicals are going to leach into the environment?

“A very real countdown also begins: once activated in China, the batteries in the magazines will last roughly ninety days.”

Electronics that last 90 days, then are disposed of. This is a good thing?

Ouch. I’m obviously a big fan of way-kewl high-tech devices, and buy a lot of them myself, but I think this sort of fuller-cost accounting is essential to evaluating new tools. I think in the long run, I’d hope that nondisposable or reusable e-ink — along the lines of the Kindle, or some use-once-and-recycle tech we can’t yet engineer — could potentially be a net reducer of waste. But that would require very careful design. Tom is part of a movement of engineers and hackers who are beginning to think about the concept of designing electronics with the eventual goal that their components can be easily disassembled and/or reused, instead of thrown out. That’s the sort of thinking we’ll need to embrace so we don’t drown in our own e-waste.

Behold a 30-ton, 10-foot-high spinning ball of steel and sodium that is intended to simulate the Earth’s magnetic field.

Why does this delightful and insane object exist? Because Dan Lathrop, a geophysicist at the University of Maryland, is trying to figure out whether the Earth’s magnetic fields are going to “flip” soon and reverse polarity. The magnetic field is generated by the spinning motions of the Earth’s 12,000-kilometer-thick liquid-iron core. Theoretically, a change in the direction or rate of spin is what flips the north/south polarity, though scientists really don’t understand how this works. We know that the field has flipped hundreds of times in the past; the rock record shows this.

However, since the last flip was 780,000 years ago, we don’t know how a flip would affect life on Earth. It could be pretty nasty: The magnetic field deflects a lot of the Sun’s incredibly nasty radiation, so if you take it away, we could all get microwaved to a crisp. (You may recall that this was the plot to the lafftastically awful sci-fi flick The Core: A military experiment Gone Terribly Awry had shut down the spinning motion of the Earth’s molten core, so a crack team of scientists had to go down and set off some nukes to get it moving again.) Now here’s the scary thing: The Earth’s magnetic field has weakened by 10 per cent since we started measuring it 160 years ago. Does this mean the core is changing speed or direction? Is it going to flip soon?

Nobody knows. So Lathrop decided that the only way to figure it out would be to build scale models of the Earth, by filling spheres with sodium — which is highly interactive with magnetic fields — and spinning them. If he can create a good SimEarth, scientists can begin designing experiments to try and deduce the laws that govern the core, and perhaps make solid predictions about the next flip, giving us time to prepare. As he notes in this interview:

The problem with doing that against the earth directly is that they can make a prediction right now, but you may have to wait 100 years to see if they were right or wrong. The experiment runs relatively more rapidly in terms of the way the magnetic field evolves. So they can make a prediction, which you only have to wait five minutes to test. And so then we can have some give and take in improving the models and building a predictive model for the earth’s field.

Lathrop’s been at this for years, but his first few spheres — only a few feet in diameter — didn’t yield useful results. So now he’s crafted that huger, 10-foot-diameter monster that you see above. To really get a sense of how berserk this thing is, check out this video: As it creaks and groans into action, it looks more like something designed to destroy the Earth than to save it. Personally, I think Lathrop should install a couple of 100,000-volt Tesla coils in the corner of his lab, so they can hurl forty-foot arc lightning over his globe as it spins in its dread revolutions. Wouldn’t do anything, of course, but it’d look awesome.

Oh, and check out the awesome schematics after the jump, below! (They’re taken from one of Lathrop’s presentations.) Viewed in cross-section, his globe looks precisely like a supervillian’s submersible/astronautical lair.

So, I was reading the half-page infographic feature “Colossal Squid Revealed” in the latest print issue of Popular Science, and, disappointingly, it was just a recitation of information I’d long known: 10-foot-long tentacles with killer hooks, check; 10-inch eyes optimized for lightless depths, check; sworn enemy the sperm whale, check; likely to rise up and annihilate humanity pretty soon; check; we are totally screwed, check.

But then I hit upon a factoid of which I’d been previously unaware:

The squid has a doughnut-shaped brain; the esophagus passes straight through the center.

That’s just superb. The infographic is online here; click through the gallery to get to the esophagus stuff.

I only discovered this now, fully a year after everyone else blogged about it, but it’s so awesome I have to write about it: A mechanical, binary adding machine that uses marbles to flip the bits. There are several gorgeous close-up pictures of the device on the web site of the designer, Matthias Wandal, but the best way to understand it is to watch that video of it in action!

I’m a huge, huge fan of projects that make digital logic visualizable — like the German geeks who created a mechanical Pong game driven by magnetic relays, or the MIT folks who built logic gates using water. Today’s computer users have no idea how computer logic works, which you could argue is a problem of cultural literay: If you don’t understand how chips “think” then you can’t understand what they’re good at and what they’re horrible at. We live in a world increasingly governed by computer logic; we owe it to kids to explain the thinking processes that run their personal Matrices, because they’ll spend their lives bumping up against the mechanosocial rulesets of Facebook or Mindbook or whatever they hell they’re wetwired into 25 years from now.

That’s why we need awesome rigs like this woodpunk engine of marbleocity. What I particularly like is that fact that it’s powered by gravity and governed by the laws of Newtonian physics, which required the Wandel to tinker quite a bit, because bouncy marbles are not the most precise bits, as it were. From Wandel’s writeup:

Also tricky was getting the rockers to consistently work. I spent a lot of time figuring out what dimensions to make them so that they would correctly work, even if two marbles arrive onto the rocker right on top of each other. I knew it was physically possible to build such a rocker, because the lego rockers I built into the original Lego marble machine had this property by a fluke. The trick turned out to be to make peak of the rocker, which divides the marbles, short enough, and the rocker shallow enough. That way, if a marble arrives before the rocker has had a chance to flip, the previous marble, which is still on the rocker, will deflect the next marble onto the other side, even if the rocker has not yet flipped.

These things cost $250, and I’m currently trying to figure out how to convince my wife that we should buy one. Since she reads this blog, I’m assuming this posting constitutes my first rhetorical salvo. And hey, it’s educational! For the kids!

I’m not joking, though; I really do believe that the “aha” factor of seeing how computer logic works is transformative. To quote my own blog post from four years ago:

Back in grade seven in 1980, I found a book in my library showing how to build logic gates out of magnetic relays. I went to Radio Shack, bought about 20 relays, and spent the next few months building increasingly complex logical operations, including little adders that could calculate the sums of binary numbers. My parents thought I’d gone insane.My favorite moment was when I built a flip-flop gate — the basis of computer RAM. It’s just a simple feedback operation: You click a switch that activates a set of relays that begin feeding electricity back to themselves, so they remain eternally on. (They’ll only turn off if you run out of electricity or if you purposely “erase” the memory by actively breaking the circuit.) I built a flip-flop circuit, flipped the switch, watched the relay click on and remain on. It was a trippy, Frankensteinan moment. I’d created a piece of memory — a device that seemed to display some tiny piece of self-consciousness. Very heady stuff when you’re 10 years old!

At any rate, when I started using computers a few years later, I had a reverse-Matrix experience with them: When I ran a program I could imagine it as this enormous football field of electromagnetic relays clacking on and off, the logic muttering to itself like a chorus of crickets at night.

It is, of course, inherently asinine to quote oneself, but I’m taking on mulligan on this one because I wanted to repeat the same story/point here and didn’t think I could rephrase it more succintly.

(Thanks to Ned Gulley for this one!)

As you’ve probably heard, the rise of noise-pollution in the oceans has caused huge problems for marine life. Animals that echolocate — like whales — are increasingly deafened by the din of shipping vessels and military sonar. Indeed, it’s apparently gotten so bad that we are now seeing a rise in collisions between whales and boats; it’s bad for the whales, of course, but if if a small vessel hits a whale, even humans can die too.

This inspired Michel André, a marine biologist and biotechnology engineer, to develop a whale-avoidance system so that boats could detect nearby whales and steer away. The problem is that any “active” system — something that sent our sonar probes — would just add more noise to the oceans and further confuse the whales. He wanted to do it passively. So he started designing an array of listening devices that would listen for the clicks and whoops of whale-call, or even the sound of rain and waves splashing along silent whales.

But here’s the really awesome part. As Gizmag reports:

A remarkable feature of his system is its ability to single out and track an individual whale among all its “family” members in the same area — a breakthrough made with the help of a West African musician. After years of research, André’s discovery that the sequence of acoustic signals transmitted by the sperm whales could be used to identify individual mammals — a process called Rhythmic Identity Measurement (RIME) — was almost by chance. In attempting to unravel the chaotic rhythms of the sperm whale clicks, he was struck by the similarity between his underwater recordings and African tribal music. A Senegalese griot (drummer) confirmed the likeness and — amazingly — was able to pick individual whales from André’s recordings through their distinctive rhythmic structures.

A whale-detection system powered by algorithms derived from African drumming. Oh yes. I love the way that musicians always wind up being the ones who can understand whalespeak better than anyone else, like that guy who figured out that whales appear to have a particular affection for the clarinet note G.

I’m coming a bit late to this one, but apparently a new study has unveiled a curious new fact about cows: They align themselves with Earth’s magnetic field.

In a the paper “Magnetic alignment in grazing and resting cattle and deer” — published in an August issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences — a team of German zoologists used Google Earth to examine images of 8,510 cattle and 2,974 deer in hundreds of locations across the Czech Republic. The result? Whether standing and grazing or resting, the cows and deer tended to align themselves with magnetic north or south. We’ve known for years than smaller mammals like birds, turtles and fish can sense the Earth’s magnetic fields, but nobody thought really big mammals could do so.

The funny part is that the scientists now wonder whether this ought to be taken into considering in the architecture of barns. As Sabine Bengall, one of the zoologists, told National Geographic News:

Begall and her co-authors also note it’s unclear why cows and deer would align themselves with Earth’s magnetism. But it could have management implications, she suggests.

“If we assume that our findings are real, we could ask what consequences does [barn] housing in east-west orientation have,” she said.

“Does it influence the animals’ physiology, as in milk production?”

Feng Shui for cows. Beyond awesome.

The other delightful part of this story is how the scientists conducted their research: Via Google Earth. They realized that it would be “difficult, or maybe impossible, to do these studies in the lab”. But Google Earth allowed them to quickly collect massive amounts of data. Indeed, that’s the remarkable thing here. Anyone — you or I — could have done this study, using data that Google has already collected.

UPDATE: Thanks to Ian York and Lisa Mandle for sending me a copy of the paper! I’d wanted to see if it included any of the Google Earth images so I could excerpt them, but sadly it didn’t. That current picture I’m running above is the cow-herd shot that accompanies the story in National Geographic.

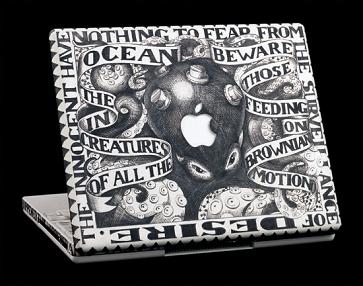

I’m in love. Michael Dinges is a Chicago artist whose latest show — “Dead Reckoning” — consists of laptops engraved with spectacularly cool images, as well as a set of brass instruments styled after traditional sea-faring navigational tools (examples of those below, after the jump). When I saw the octopus-etched Apple laptop above, my heart began beating in a Fibonacci sequence. I should be unconscious any minute now.

In addition to being sumptuously awesome-looking, Dinges’ work is quite thought-provoking too, because he’s chewing over the relationship between how we use our tools to explore and exploit the natural world. You can read his artist’s statement here, or check out the essay about his work that the Packer Schopf Gallery — where this stuff is currently on display — commissioned, by Antonio Pocock:

When displayed together, Dinges’ obsolete navigational and timekeeping instruments and his engraved dead laptops present the evolution of technology and comment on our impulse and attempts to navigate the world. Estimating a ship’s location by tracking direction and distance traveled from a previously determined position using charts and instruments, rather than by direct observation of the stars and sky, is called “dead reckoning.” This term suggests that mediating experience and knowledge with various calculations and instruments removes man from the “live” world.

If we compare the manipulation of a seventeenth-century backstaff, for example, to that of a computer, we see that the use of navigation technology has become increasingly “dead,” or removed from reality. A backstaff required man to use his full body to gather information about his surroundings and to possess a command of physics to interpret that information. A computer hides its internal functions from the user, who passively absorbs the information displayed on its screen. As technology advances, the experience of navigation becomes increasingly abstract.

Pocock’s essay is a little overlarded with needless critspeak, but she does a great job of illuminating the cool areas Dinges explores: The history of sailors and warriors etching their tools to imbue them with mythic dimensions; the idea of navigation as a quest for meaning; the way that tools shape and constrain our thinking; the complexity and fragility of ecosystems; Brownian motion; Ouija boards; squirrels, and more! Man, I hope this show travels to New York so I can see firsthand.

Click on “more” to see images of a few of Dinges’ brass instruments …

Okay, the war over “invisibility cloaks” has officially begun. A team of Chinese scientists have just announced that they’ve figured out how to defeat invisibility technology — and render “invisible” objects visible.

You may remember the famous experiment in 2006 in which Duke University scientists created an “invisibility cloak” — a wave-morphing shield that allowed them to render an object mostly invisible to microwave beams. (Check out a video of their original demonstration here; it’s pretty cool.) This generated endless news stories that breathlessly invoked Harry Potter; more hilariously yet, it set off a mini-boom in researchers frantically working on their own invisibility cloaks.

Now the counterattack has begun! Next week, a team of Chinese researchers will publish a paper called “The Anti-Cloak” in the journal Optics Express (PDF copy here). In essence, they did some calculations and figured out that if you coated an object with the right anisotrophic materials — stuff that reflects light in different ways depending on the direction the light comes at it, kind of like velvet — then the invisibility cloak wouldn’t work. (To be precise, you’d need “anisotropic negative refractive index material that is impedance matched to the positive refractive index of the invisibility cloak.”) Presto: The invisible becomes visible!

As they put it in their press release:

While an invisibility cloak would bend light around an object, any region that came into contact with the anti-cloak would guide some light back so that it became visible. This would allow an invisible observer to see the outside by pressing a layer of anti-cloak material in contact with an invisibility cloak.

I have to say, I laughed out loud with delight when I heard about this paper. This is the sort of perfectly demented, cackling scientific duel you normally only encounter in golden-age comic books. Freeze ray vs. anti-freeze ray! Antigravity vs. supergravity! At this rate we’ll wake up to find CNN footage of rival teams of scientists in 80-storey-tall mechas, duking it out with tachyon-particle cannons over the desolate ruins of Tokyo, and arguing about who’s got more citations.

This is lovely: A “timescanned video” project by some students at NYU’s Interactive Telecommunications Program. Basically, they took panoramic video shots of various street scenes in New York, and then smooshed them into these wonky, crazy, stretched-out still images. As they describe it on their site:

We wanted to experiment with capturing only one small slit of the camera’s image and adding it to the end of an image compiled in real-time using Processing. This allowed us to create extremely long panoramic images composed of thousands of small “slits” of time.

Truthfully, their description is so vague I can’t figure out exactly what sort of algorithmic hoodoo they used, but it doesn’t matter; they’re still fun to look at. Sort of ghostly, actually: The time distortion renders the background mostly normal — if someone wavy — while the people turn into odd, Flatland-like two-dimensional citizens.

The New York Times got about 80 reader comments on my recent story on “ambient awareness”, and they asked me to respond to a few readers’ questions. I wrote up a bunch of replies today — and the text is, hilariously, about half the length of the original piece!

My replies are now online here at the Times’ site, and I’ve archived a copy below. (About that graphic above: While composing my replies to the readers, I — of course — Twittered about the fact that I was composing my replies, whereupon the Times editors took a screenshot of my Twitter feed, and used it as a graphic to head up my replies. Very meta!)

As a nearly-78-year-old who didn’t even SEE a dial telephone till she was 10, I’m more than shocked about the ambient intimacy described. I’m an omigod reader of this article! Yet I’m still teaching, and I know my students use these tools.I think I’ll bring the topic and the article up in class next week and ask my students how they fit into the picture described by Clive Thompson. I can’t decide if I’m a Luddite old fogy who just doesn’t get modern technology (last fall, my “kids” couldn’t believe I’d never touched an iPOD or seen a text message!) or who thinks there are some details of my life I’d just as soon keep private.

Is this a generation gap? And how will these GenY people feel when their pasts catch up with them during job applications or dating relationships?

— Jan Bone, Palatine IL

Wired News just published my latest video-game column, and it’s a pretty fun subject. It’s about how teenagers, while deducing how to beat bosses inside online video games, have unwittingly stumbled upon the scientific method. It’s online for free at Wired’s site, and a copy is archived below!

How Videogames Blind Us With Science

by Clive Thompson

A few years ago, Constance Steinkuehler — a game academic at the University of Wisconsin — was spending 12 hours a day playing Lineage, the online world game. She was, as she puts it, a “siege princess,” running 150-person raids on hellishly difficult bosses. Most of her guild members were teenage boys.

But they were pretty good at figuring out how to defeat the bosses. One day she found out why. A group of them were building Excel spreadsheets into which they’d dump all the information they’d gathered about how each boss behaved: What potions affected it, what attacks it would use, with what damage, and when. Then they’d develop a mathematical model to explain how the boss worked — and to predict how to beat it.

Often, the first model wouldn’t work very well, so the group would argue about how to strengthen it. Some would offer up new data they’d collected, and suggest tweaks to the model. “They’d be sitting around arguing about what model was the best, which was most predictive,” Steinkuehler recalls.

That’s when it hit her: The kids were practicing science.

There are many weird things about the giant Humboldt squid, but here’s one of the strangest: Its beak. The squid’s beak is one of the hardest organic substances in existence — such that the sharp point can slice through a fish or whale like a Ginsu knife. Yet the beak is attached to squid flesh that itself is the texture of jello. How precisely does a gelatinous animal safely wield such a razor-sharp weapon? Why doesn’t it just sort of, y’know, rip off? It’s as if you tried to carve a roast with a knife that doesn’t have a handle: It would cut into your fingers as much as the roast.

This question has haunted many a marine biologist. So recently a team of materials scientists at the University of California decided to carefully examine the physical properties of the beak. Their discovery? The beak contains a huge gradation of stiffness: The tip of the beak is 100 times more rigid than the base of the beak — so the base can blend easily with the surrounding flesh. Water is the key to the proper functioning of this gradient: If the beak is dried out, the soft base calcifies until it’s nearly as dense and rigid as the peak. (You can read their paper — “The Transition from Stiff to Compliant Materials in Squid Beaks” in PDF format here.)

Now the scientists are trying to figure out how to artificially replicate this remarkable gradient, because it’s so radically different from the way we humans traditionally develop materials. We know how to create materials that are really stiff or really soft, but not ones that slide gradually from one to the other extreme. As they note in a press release …

… most engineered structures are made of combinations of very different materials such as ceramics, metals and plastics. Joining them together requires either some sort of mechanical attachment like a rivet, a nut and bolt, or an adhesive such as epoxy. But these approaches have limitations.

“If we could reproduce the property gradients that we find in squid beak, it would open new possibilities for joining materials,” explained Zok. “For example, if you graded an adhesive to make its properties match one material on one side and the other material on the other side, you could potentially form a much more robust bond,” he said. “This could really revolutionize the way engineers think about attaching materials together.”

This is biomimicry, of course — the art of designing new artificial materials based off of superweird stuff found in the animal kingdom. It’s thus an important rationale for planet-saving conservation, because every time a species dies off, it often takes some remarkable physical property with it — something that, if we replicated, we could use to build bridges, save lives, or whatnot. (Actually, this is the area that Debbie Chachra, a friend of mine and longtime Collision Detection commentor, works in. She’s been studying the unusual properties of bee spit or something. Debbie, could you clarify this in the comments area if you’re reading this?) When people used to talk about the important of preserving biodiversity, they mostly worried about medicines: i.e. the fact that bugs and trees in the Amazon rainforest contained zillions of potentially useful drug compounds. But now we’re learning more about the importance of understanding the physical engineering behind these marvels of animal life.

UPDATE: Debbie posted a comment to explain that she is indeed working on the bee-spit problem, and she also laid out a great analysis of the utility of this gradient problem. Check it out …

(That picture above is from National Geographic’s online archive!)

I got a few emails from folks wondering “where have all the old comments gone?”

If you look at my old entries, all the comments are gone. This is because I changed my commenting system: I’ve recently started using Disqus to manage my comments, because the old Movable Type comments were too susceptible to comment spam — and, worse, my hosting service Pair.com had the unfortunate habit of shutting down my comments if the script (mt-comments.cgi) got pounded by a comment spambot.

At the moment, Disqus doesn’t have a tool for importing all the thousands of old comments I have in my Movable Type comment database. But Disqus has promised to create such a tool soon, and when they do, I’ll slurp all the old comments into Disqus so they reappear.

Last week I was on vacation in Connecticut, and somebody left the patio door open for a few hours. Pretty soon the kitchen was filled with about 50 huge, fat, disgusting flies, and I was left with the even more huge, fat and disgusting task of running around killing them all with a rolled-up newspaper. And of course, I quickly discovered something everyone has figured out: Flies are really good at avoiding a swatter.

How do flies do it? Scientists and chefs have argued about this for years. Some theorize that the flies can sense the approaching air shock wave generated by a rolled-up newspaper. But nobody ever really knew. So a group of US scientists led by Caltech’s Professor Michael Dickinson decided to swat at some flies while filming them in super-slo-mo. According to the BBC …

… the researchers discovered that long before the fly leaps it calculates the location of the threat and comes up with an escape plan.Flies put their bodies into pre-flight mode very rapidly: Within 100 milliseconds of spotting the swatter they can position their centre of mass in the right way so that a simple extension of their legs propels them away from any threat. [snip]

“Our experiments showed that the fly somehow ‘knows’ whether it needs to make large or small postural changes.

“This means the fly must integrate visual information from its eyes which tell it where the threat is approaching from, with mechano-sensory information from its legs, which tells it how to move to reach the proper pre-flight pose.”

So: What advice are we to glean from this? Unfortunately, Dickinson suggests that to kill a fly you should “aim bit forward of its location and try and anticipate where the fly will jump when it first sees your swatter,” which seems kind of nuts: What sort of crazy latent ninja abilities do you need to harness to anticipate where a fly is going to jump?

Even funnier is that BBC video of the fly-recording experiment, because the BBC bills it as “high resolution video of a fly avoiding a swatter”, but when you click on it you’re first subjected, without warning, to a 30-second long tourism ad for the city of Seoul. So when I clicked on it and found myself watching a long panning shot of some Korean dude wandering around downtown Seoul, doing some shopping, eating dinner, I thought, wow, this is one seriously sophisticated fly.

UPDATE: James Sherrett stopped by to post a totally awesome guide to fly-swatting, based on his summers gutting fish — a necessarily fly-infested task — in Northern Ontario. Go check out the comments to read it!

Today, the New York Times Magazine is publishing an article I wrote about “ambient awareness” — the way that micro-updating tools like Twitter and Facebook give us a constant, floating sense of what everyone we know is doing, all the time. The piece is online free at the Times’ site, and I’ve put a copy below for archival purposes too.

That graphic above is a snippet from Peter Cho’s wonderful illustrations that accompany the piece. Cho did a lovely job of taking a pretty amorphous concept and turning it into evocative imagery!

Here we go:

I’m So Totally, Digitally Close To You

How News Feed, Twitter and other forms of incessant online contact have created a brave new world of ambient intimacy.

On Sept. 5, 2006, Mark Zuckerberg changed the way that Facebook worked, and in the process he inspired a revolt.

Zuckerberg, a doe-eyed 24-year-old C.E.O., founded Facebook in his dorm room at Harvard two years earlier, and the site quickly amassed nine million users. By 2006, students were posting heaps of personal details onto their Facebook pages, including lists of their favorite TV shows, whether they were dating (and whom), what music they had in rotation and the various ad hoc “groups” they had joined (like “Sex and the City” Lovers). All day long, they’d post “status” notes explaining their moods — “hating Monday,” “skipping class b/c i’m hung over.” After each party, they’d stagger home to the dorm and upload pictures of the soused revelry, and spend the morning after commenting on how wasted everybody looked. Facebook became the de facto public commons — the way students found out what everyone around them was like and what he or she was doing.

But Zuckerberg knew Facebook had one major problem: It required a lot of active surfing on the part of its users. Sure, every day your Facebook friends would update their profiles with some new tidbits; it might even be something particularly juicy, like changing their relationship status to “single” when they got dumped. But unless you visited each friend’s page every day, it might be days or weeks before you noticed the news, or you might miss it entirely. Browsing Facebook was like constantly poking your head into someone’s room to see how she was doing. It took work and forethought. In a sense, this gave Facebook an inherent, built-in level of privacy, simply because if you had 200 friends on the site — a fairly typical number — there weren’t enough hours in the day to keep tabs on every friend all the time.

It’s been an awfully long time since I blogged — seven months, to be precise. There’s a story behind that, which I’ll tell in a few days, but for now: Welcome back! Particularly to anyone who put me in their RSS feed long ago and then sat around listening to the sound of crickets for half a year.

In the meantime, I hope everyone likes the new design! It’s the excellent work of Andrew Hearst, an old friend of mine who is a superb graphic designer and webcrafter (and whose blog Panopticist is over here). I’d been meaning to revamp this place for a long while. Indeed, I swiped the original design from Blogskins — back in 2002 when I created Collision Detection — and never touched the code again, mostly out of laziness but partly also because, having no HTML-fu, I was worried I’d accidentally remove some tag that would collapse the entire Internet. The design I launched with was called Carabeth Blue, created by Tyler Cole; Andrew retained some of my favorite parts of while making something entirely fresh and new.

Anyway, I have about 900 things to blog that I’ve gathered in the last few months, so I’d better get busy …

I'm Clive Thompson, the author of Smarter Than You Think: How Technology is Changing Our Minds for the Better (Penguin Press). You can order the book now at Amazon, Barnes and Noble, Powells, Indiebound, or through your local bookstore! I'm also a contributing writer for the New York Times Magazine and a columnist for Wired magazine. Email is here or ping me via the antiquated form of AOL IM (pomeranian99).

ECHO

Erik Weissengruber

Vespaboy

Terri Senft

Tom Igoe

El Rey Del Art

Morgan Noel

Maura Johnston

Cori Eckert

Heather Gold

Andrew Hearst

Chris Allbritton

Bret Dawson

Michele Tepper

Sharyn November

Gail Jaitin

Barnaby Marshall

Frankly, I'd Rather Not

The Shifted Librarian

Ryan Bigge

Nick Denton

Howard Sherman's Nuggets

Serial Deviant

Ellen McDermott

Jeff Liu

Marc Kelsey

Chris Shieh

Iron Monkey

Diversions

Rob Toole

Donut Rock City

Ross Judson

Idle Words

J-Walk Blog

The Antic Muse

Tribblescape

Little Things

Jeff Heer

Abstract Dynamics

Snark Market

Plastic Bag

Sensory Impact

Incoming Signals

MemeFirst

MemoryCard

Majikthise

Ludonauts

Boing Boing

Slashdot

Atrios

Smart Mobs

Plastic

Ludology.org

The Feature

Gizmodo

game girl

Mindjack

Techdirt Wireless News

Corante Gaming blog

Corante Social Software blog

ECHO

SciTech Daily

Arts and Letters Daily

Textually.org

BlogPulse

Robots.net

Alan Reiter's Wireless Data Weblog

Brad DeLong

Viral Marketing Blog

Gameblogs

Slashdot Games